Incidental Wit

I remember thinking atomic decay, I remember knowing bells. I remember flagging down an ambulance at the end of the driveway, pointing at a window. Some come lately glow. Some frost pretending diamond, diamond.

What spree to claim loneliness like that. Like eye. Like blue, blue eye.

We’re taught young not to lean out of windows unless we mean it. Singing isn’t sin just because someone told you not to do it. It’s incidental sound that wits until it’s known. It wits into your stem & loves your frontal lobes.

It slows. It’s slowing. It’s the closest I’m coming to absolute cold, the weather dead & gleaming. A lake with sun strings clipped into it. God is a barber & he’s just sweeping up.

Tonal Memory

A page may link with a tune, but not a lung. Why does a sad hand linger like it does? I asked a wire where it hid its salt. It looked at me & pointed at the particles in my loom.

*

When the basil plant flowers you can tell me about your day. Until then, lay in this leaf pile. Try to sing about the villages we made by mistake.

*

In my dreams I only paint by numbers. As for colors I have seven shades of red. Look at my fingers. Look at my colors. Look, I can speak in flames.

*

A soon to be new moon of Saturn befriended my textbook Kepler. First time I took tea without milk. It’s OK.

*

When you mentioned that you might go away I thought “yellow colonial houses,” I thought “typewriter keys.”

*

A wet, black dog bounced in the back of the truck. I peeled plastic off the dashboard. The CB radio glowed. Like a bowl of lime yogurt, kind of.

*

In every loom there is a lake. When the lake goes away, loam remains. Loam is a reminder that live things are sour, that silence indicates a coming season.

*

In the woods the ground was glowing. My father crept back to the road. He took small sips of the moon the way boys did in the 50s.

*

I smoked a joint on the ice . . . every window threw a different type of light. Every thought was set in a different type.

*

A page may link with a lung, but the thought needs salt in its cup. Salt in a cup can clear the blood slightly, but only slightly.

*

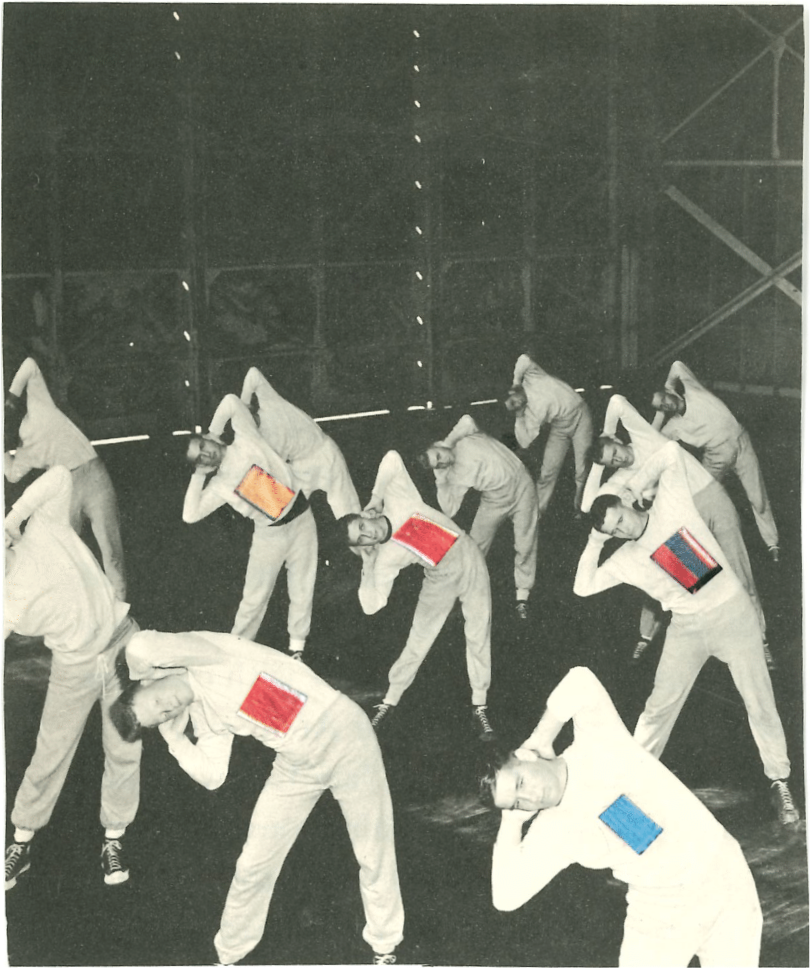

We’d sit in a circle & roll the block. Roll the block & see what color came up. See what color came up & sing a song. Sing a song that had leaves in it. Leaves in it or snow. Snow or a red blotch on your cheek. Your cheek is like the trees. The trees I’d paint with berries.

*

What it’s like to swim in the rain. What it’s like to pee in the woods (feels good). What it’s like to lay in a pile of leaves & sing about nothing, once.

*

I led a book into the room. I told its verbs to vaporize, to play inside the light. Instead they got naked and danced each other dizzy.

*

You tore your dress. You patched it with peach skins. My sometimes god gave you an A+. I gave you blueberries.

*

You mentioned becoming president, that I could be your secretary of secrets. I declined, having too many foreign interests.

Blake Bergeron is an MFA candidate at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. His work can be found in Route Nine, Incessant Pipe and The Alembic. He lives in Florence, MA.