the prose poetry magazine

elsewhere

- issue 26

- fall 2025

- Ace Chu

- Brian Hoey

- Hazelle Lerum

- Lewis LaCook

- Shy Parris

- Mike Puican

Ace Chu

PRAYER

The body needs tenderness, and softness. I talk myself down like an animal on the way to the slaughterhouse. The chicken is held tightly underarm, with just enough pressure to let it know that it cannot escape. A firm palm on its neck, soothing words and strokes. My fingers interlace in earnest– I am in communion with myself. Blood from both sides, hammering on the double boundary of skin, desperate to come full circle. Shut, my eyes become two lonely suns. Each rotates on its own axis, pulling my brain along in orbit, scrambling my days and nights. Gently, with my thumb, I stroke the back of my thumb.

THE GREAT FIRE

(After the Chatuchak Market fire)

If you believe in an afterlife for animals, there is some comfort. Once-shackled, cages of bone melt, giving way to a skyward stampede of cinder, souls, and the in-between. The ark burns, yielding to the relief of water. If there is nothing after death then we cannot look away from the end. Flesh foundry, fear in a chicken in a snake in a cat in a dog. Fat oozing from between bars, oven set too high. They could not have gone quietly, bodies breaking against unforgiving steel. Every cry at once, the sound that must have rung out when God, in a single moment, birthed every animal on Earth.

Brian Hoey

On afterlives

My love, I will be moral enough for both of us, so that when the resurrection comes and we are both reborn in the body of Adam, I will spot you amid the throng; the identical animated, the masses of the same flesh, with infinitely varied minds inside, as if fingerprints or clovers were all the same but we knew in our hearts they were as individual as social security numbers; the same body again and again, with eyes shorn wide, saying excuse me in a babel of tongues—all lost, now—crushing limb to limb and seeking perhaps a dozen, perhaps two, among the billions who have ever lived, who might know their true names, and their true bodies, long lost too, and the missed loves and favorite breakfasts and ugly sobbing films that were housed in those bodies; I will cut through them like a scythe, I will sight you from room to room and across wide fathoms, and I will shoulder past billions of Adams (with eyes shorn wide), saying excuse me, excuse me.

Hazelle Lerum

To Hajime Sorayama's Girls

We are full of mourning fluids, just under the surface. We are an abundance of movement, just under the surface. Blood, lymph, metropolitan tubes of chewed-up food—You are an icon of chrome, metonymy for the city, your body not just your body, but a proving ground for politicians to celebrate your metroid superiority, the proletariat of your pipes. The labor that makes you lean. The ethic that makes men's jaws square. Here's to you, Miss Metropolis, with hair Aquanetted to your scalp: your body is the city. You are so much more than a tits-and-waist fuck tease. You are diesel and chrome, you are hydroelectric, and the men that move through your body are building undeniable things, inevitable things, with their honest hands.

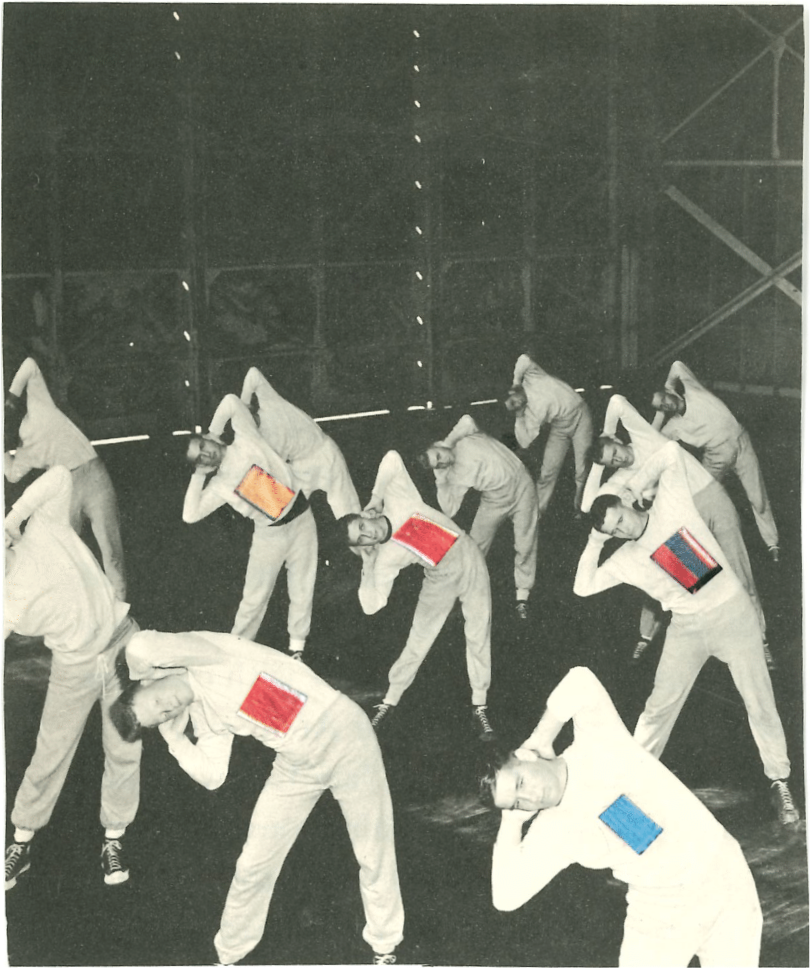

There Is No Ethical Archaeology Under Capitalism

Peaches are wet, but the pit always has the manners to be dry. The bone collection is yellowish and slightly greasy, not dry and bleached like ones in the woods. They are sharp sponges, weeping yellow grease like water out of a stone. At night, I see women and men's bodies overlapping in an intangible heap: bone contortionists in a shallow drawer. No matter how much the students wring their hands, they cannot match this stupendous pose.

Lewis LaCook

Holding hands under the bed

When you become a monster is it because of your sense of taste or is it because you are composed of dead parts like everyone else?

Do you know the history of your own hands? Is the hair creeping over the backs of them soft like the tentative fuzz on a baby's crown or is it coarse like hackles?

Does it smell faintly of sulfur?

Do children run from you? Do adults cross to the other side of the street? When they do, do you ruminate for some moments on the taste of their flesh?

Would it be sweet? Salty? Sour?

Was your love of desolation a clue to your monstrous future?

Was it the night light? Did you need a way to see your dreams? Why did it matter so much, being able to see what was coming for you?

How long do you think the recognition would last before everything inevitably went dark again?

What concern is it of yours whose maw you fall into, as long as you do it with grace and a sense of style?

What if that maw turned out to be your very own, seeing as how it was you who was becoming a monster?

Don't you ever feel cramped, hiding under the beds of nervous children? Do their restless dreams fall in slow flakes around you on the floor, smothering you with sighs?

When a little arm slips from the confines of the comforter and dangles from the edge, how do you stop yourself from holding its hand?

Shy Parris

How to Tell The Story of My Father's Death:

Cowie goes to a party with Uncle Sprangy. And Reds calls Cowie and says be safe so Cowie takes a cab home. And the cab driver is an artist so he origamis his car around a lamppost. And Sprangy buries his baby brother and Reds buries her best friend and Shy trades an abstraction for an apparition. One year, my father sent a birthday card to me and signed it 'Your copilot.'

Cowie leaves behind two children who are not siblings. A father whose last magic trick was a disappearing act. A father who is only a character in everyone else's stories. At 11, I was too busy to keep my promise to call and I've kept myself busy ever since. Reds is a ghost town until she asks Cowie to stop haunting her. We don't hear from Sprangy again. Figure we'd know if he died - every story finds its way home eventually.

(first)

Mike Puican

World Held Still

A childhood and its addictions, whole neighborhoods tinged with sorrow. It's not certainty but the stories that pulse underneath as we cross into language. Match, breath, Uno card, furniture movers with the sound off. Sometimes words are just this. Sometimes I hear, in what seem to be unearned moments, the wound closing. Eventually we put aside grief to write the poem about grief, then cry as we read it to thirty people in a bookstore. No ordinary moments, ever. ♦